Managers of large sites must balance search AI with navigation IA

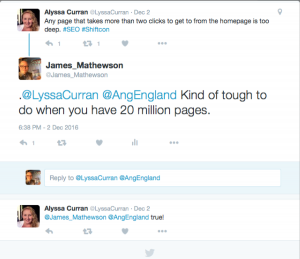

My job involves building content systems and platforms for the world’s largest private digital publisher—IBM. Most of the people I talk to outside of IBM have no idea of the size and scale of our publishing efforts. Here is an example of a Twitter conversation related to the topic:

The goal is no different for small sites and large sites: you need to help your users find the content that answers their questions in the fewest number of clicks. But as a site scales up, the level of difficulty in marking up and otherwise tagging content for findability increases exponentially. At a certain point, tagging alone can make findability worse than semantic search without tagging at all. Incorrectly tagged content surfaces irrelevant experiences to users.

When you get over 100 products at perhaps 100 pages per (counting all your user documentation), you reach a point of diminishing returns on marking up content for search engines and navigation systems. Humans are very error-prone when they tag things, especially if multiple tags apply to one piece of content. Taxonomies grow beyond human abilities to manage and use them manually. There are all kinds of ambiguities between related tags. And most companies change their product names or introduce new products faster than the taxonomy managers can keep up.

The answer to these problems is to give humans augmented intelligence (AI) to develop better taxonomies, to do a better job with content markup, and to find relevant content even when it is not well-tagged. That’s what this article is about.

Cognitive search: The antidote to poor tagging

A decade ago, I was a taxonomist and content strategist frustrated by these issues. At a certain point, I reasoned that a good search engine would help users find the most relevant content on our huge site with less effort than navigation. Our data showed that users preferred search to navigating through our megamenu of options. Besides the problems with choosing the right options for the menu, there are human limitations to megamenus. Humans don’t like long lists of things. Our brains get easily overwhelmed and, as cognitive misers, we prefer fewer options, shorter sentences and paragraphs, etc.

The psychological research on this is uncontroversial: humans can only parse seven plus or minus two things at a time—words in a sentence, sentences in a paragraph, menu items, etc. When you have a megamenu with dozens or even hundreds of items, you overwhelm users with options. Their only recourse is to use search. Hence my tweet response above.

The only refuge of companies with such large sites is to build internal search engines that automatically find content users are looking for. This view is controversial in our field because of two prevalent myths:

- Users hate search. I have attended several conference talks where the speaker says, “if you force your users to search, you failed them.” I honestly don’t know where this myth came from, but it is wrong. If users hate search so much, why do they love Google so much? The answers are: users hate crummy search experiences. But they love good ones.

- Search is just about keywords. Sure, keywords are important, but not as exact-match entities. Keywords are important because of their meaning. If you try to build a search engine that just matches query strings to the frequency, density, or prominence of keywords in content, you will fail. This is essentially what Lucene does, and it is woefully inadequate—by itself—for large sites. What you need is semantic search, which doesn’t just match queries to keyword strings, it matches content to the the searcher’s intent implicit in the query.

Semantic search engines use natural language processing and machine-learning to find the content most relevant to a searcher’s intent. At least that is the goal. If you had such a system on your site, users would use search most of the time. Most sites struggle to offer anything close to the ideal. On average, even for large sites, about 10% of visits involve search. The rest of your users expend huge cognitive effort digging through megamenus to find content that might answer their questions or solve their problems. Or they go back to Google, and maybe they click on your search results if you happen to rank against your competitors. If their initial experience with your search and navigation is poor, they prefer to try your competitors’ sites first. For these reasons, building a semantic search experience should be job number one for managers of large sites.

But how do you get started? Start by looking at semantic search engines. There are several commercial ones available. But merely installing a semantic search engine isn’t enough. It’s not a magic bullet. All AI systems must be trained. Chances are, your content writers don’t use conventional meanings of common words in your industry. More likely, different units within your company use the same terms differently. Add this complexity to your changing brand names and product portfolios, and the challenge is increasingly about training your search engine on your content.

Machine-learning in site search involves developing a feedback loop that elevates results that users click and engage with and pushes results down that have low clicks and high bounce rates.

For your most common queries, the feedback loop is the best approach because you likely have multiple pages that could satisfy the user intent of the query. But for uncommon queries, or so-called “long tail” queries, you might only have one good page that answers the question implicit in the query. For these, you need a system that tags the pages to help the search engine recognize their relevance to longer queries. Even though these queries might only occur once a month, there are so many of them, they typically constitute the majority of your user queries.

Cognitive content markup

While you need to train the search engine on your content—especially for common queries—you also need to train your content to help out your search engine, especially for uncommon queries. Cognitive search doesn’t eliminate the need to tag your content, it just makes it less urgent to do so. While you are marking up all your long-tail content, at least you can serve relevant content to your users for their common queries. For everything else, there is no substitute for good tagging. But how do you tag content well considering how error prone human taggers and taxonomists are?

The same AI systems that help you serve relevant content to your users can help your taxonomists build better controlled vocabularies. They can also help content practitioners mark up your content more accurately. At IBM, we use Watson Explorer for both, but there are other cognitive technologies that can analyze massive quantities of content and extract the most useful taxonomic values from them. You can try the AlchemyAPI, for example, to extract the most common values on a large site. Then you can use classifiers to build taxonomies from the term extraction. Finally, you can test and iterate on the values you use to make finer adjustments, using human experts to validate relevance.

If all this talk of classification makes your head swim, don’t worry. You’re not alone. But it is not as difficult as it seems. Anyone who has studied biology knows that a big part of that field is classifying animals and plants into genus and species, etc. The process is very similar for content classification. You have buyers and buyer journey stages and discrete actions in each stage. At each stage in the journey, different types of content work better because they suit the purpose. If you model your content classification according to your buyer journeys, you’ve made a good start in helping search and navigation systems serve the right content to your target audiences, aligned to their user intent.